Go On Location: Film Noir Locations in Los Angeles

Now listen here, dames and gents! The landscape of Los Angeles has been captured in countless film noirs over the years. Though many of the shadowy alleyways, smoke-filled buildings and dark corners featured in them no longer stand, there are a few locales that remain intact. You’d better read on for a list of ten L.A. film noir locations - if you know what’s good for you.

NOTE: Several locations are private residences, please be respectful when visiting.

“Act of Violence” - Glendale Transportation Center

The intensely ominous final scene of the 1948 film noir Act of Violence plays out against the beautiful backdrop of the Glendale Amtrak/Metrolink Station, aka the Glendale Transportation Center. Commissioned in 1924 by the Southern Pacific Railroad, the ornate Mission Revival-style terminal was designed by architect Kenneth MacDonald Jr. and structural engineer/architect Maurice Couchot. Originally known as the Glendale Southern Pacific Railroad Depot, the gorgeous station has been featured numerous times on screen in productions such as Bulletproof, Big Business Girl, College, Girl Missing, Horse Shoes, One More Chance and Here Comes the Groom. The site also had a brush with history on Sept. 20, 1959, when Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev stopped there for about six minutes during his visit to Los Angeles.

Contrary to popular belief, the Glendale Transportation Center is not where Barbara Stanwyck dropped off Fred MacMurray in Double Indemnity. In reality, the terminal used in that flick was the old Burbank Southern Pacific Station, which once stood at 201 N. Front St., but was partially burned down in 1991 and then completely demolished a few years later. Today, the Burbank Metrolink Station stands on that site.

"Angel's Flight" - Angels Flight

Originally opened in 1901, Angels Flight is a funicular that takes passengers from its Lower Station on Hill Street across from Grand Central Market, up 298 feet to the Top Station at California Plaza on Bunker Hill. Fare for the "shortest railway in the world" is $1 each way, or $.50 for Metro TAP Card users. A souvenir round-trip ticket is available for $2. Angels Flight is open daily from 6:45am to 10pm, including weekends and holidays.

Angels Flight has starred in generations of films, including film noirs like Criss Cross (1949), the 1951 remake of M, The Turning Point (1952), Cry of the Hunted (1953), and Kiss Me Deadly (1955).

A late-era film noir, Angel's Flight (1965) is described by AFI as "prized for its location coverage of [LA's] Bunker Hill neighborhood, which was slowly being razed when filming took place." The low budget thriller stars William Thourlby as alcoholic reporter Ben Wylie, who is on the trail of the "Bunker Hill Killer" - an exotic dancer named Liz (Indus Arthur). The climax takes place at the funicular.

Other appearances include The Glenn Miller Story (1954), The Exiles (1961), The Muppets (2011), La La Land (2016), and TV shows like Perry Mason (both the original and the 2020 HBO series) and the classic Dragnet. Season 4 of the Amazon series Bosch, which is based on Michael Connelly's sixth Bosch book (also called Angels Flight), features LAPD detective Hieronymus "Harry" Bosch investigating the murder of an attorney on Angels Flight, which appears throughout the season.

“Chinatown” - The Prince Restaurant & Bar

One of L.A.’s most historic eateries, The Prince Restaurant & Bar was originally established as The Windsor Inn in the courtyard of the Windsor Apartments in 1927. The site was taken over in 1949 by a man named Ben Dimsdale, who moved it inside to the building’s first floor, shortened its name to “The Windsor” and changed the menu to French-inspired fare. Thanks to the space’s proximity to the legendary Ambassador Hotel and its dimly-lit, gorgeous interior, it wasn’t long before the place became one of L.A.’s finest eateries, serving everyone from American presidents to A-list actors. The restaurant changed hands again in 1991, was renamed “The Prince” and the menu given a Korean flair, but the ornate interior was left intact and has not been touched to this day.

In 1974, The Windsor masked as The Brown Derby, where Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) admitted her past dalliances to J.J. Gittes (Jack Nicholson) in Chinatown. Miraculously, the restaurant still looks exactly the same today as it did when Dunaway sipped “a Tom Collins with lime, not lemon” there over four decades ago. The site is a location manager favorite and has also appeared in Mad Men, Thank You for Smoking, The Defenders, Crank, Prime Suspect, Criminal Minds and New Girl.

"Criss Cross" - Union Station

Known as “the last of the great train stations,” Union Station is the largest railroad passenger terminal in the Western United States. The Mission Moderne style station was designed by the renowned father-son architect team of John and Donald Parkinson. Opened in May 1939, Union Station is a major Southern California transportation hub, serving daily commuters with Amtrak long distance trains, Amtrak California regional trains, Metrolink commuter trains, and several Metro Rail subway and light rail lines. Union Station was added to the National Register of Historic Places in November 1980. Union Station hosted the 93rd Academy Awards in 2021 and is a star in its own right, appearing in decades of films such as Blade Runner, The Dark Knight Rises, Pearl Harbor and numerous film noirs.

Filmed partially on location at Downtown LA's Bunker Hill, Criss Cross (1949) stars Burt Lancaster as armored car driver Steve Thompson and Dan Duryea as mobster Slim Dundee - they're plotting a daytime caper and are rivals in a love triangle with Steve's ex / Slim's wife Anna (Yvonne De Carlo). The interior and exterior of Union Station appear in an extended scene, and Angels Flight can be seen in the background when De Carlo is standing at the window of a Bunker Hill hotel.

Film Noir Foundation founder and TCM Noir Alley host Eddie Muller named Criss Cross as No. 2 in his list of Top 25 Noir Films: "De Carlo in the parking lot pleading straight to the camera might be noir's defining moment." Look for a young Tony Curtis burning up the dance floor in his first film appearance!

“Cry Danger” - Howard Hughes Headquarters

For decades, Howard Hughes oversaw the operations of his many industries, including Trans World Airlines, RKO Pictures and Hughes Tool Company, at this massive Art Deco Moderne-style building. Iconic films such as Hell’s Angels and The Outlaw, which were produced by Hughes’ Caddo Motion Picture Company, were cut on the premises. Howard Hughes Headquarters also appeared onscreen in RKO Pictures' 1951 film noir Cry Danger as the building where newly-sprung ex-con Rocky Mulloy (Dick Powell) drops Nancy Morgan (Rhonda Fleming) off at work. The stunning structure, which sits on the corner of a quiet, unassuming side street in Hollywood, looks exactly the same today as it did on screen more than six decades ago. The building also played itself in Martin Scorsese’s 2004 Howard Hughes biopic The Aviator.

"D.O.A." - Bradbury Building

Located on Broadway across from Grand Central Market, the stunning Bradbury Building has appeared in movies, TV, music videos, and is mentioned frequently in literature. Built in 1893, the building was featured prominently in the 1982 sci-fi classic Blade Runner and appeared in Best Picture winner, The Artist (2011). The Bradbury was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1971 and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1977, one of only four office buildings in LA to receive the honor.

D.O.A. (1950) stars Edmond O'Brien as accountant Frank Bigelow, who's been poisoned and has 24 hours to solve his own murder. The Bradbury appears as the Phillips Import-Export Company in the climactic confrontation between Bigelow and his killer. Film noir fans can also spot the Bradbury in classics such as Chinatown (1974), Double Indemnity (1945), I, The Jury (1953) and M - the 1951 remake of Fritz Lang's original German film features the Bradbury in a manhunt that spans the basement to the roof.

“Double Indemnity” - Dietrichson House

At the beginning of the 1944 noir classic Double Indemnity, Walter Neff (Fred MacMurray) approaches a towering Mediterranean-style dwelling and says, “It was one of those California Spanish houses everyone was nuts about 10 or 15 years ago. This one must have cost somebody about thirty thousand bucks – that is, if he ever finished paying for it.” Though the pad’s price tag has grown exponentially over the years, the home itself still looks much the same as it did on screen more than 70 years ago. Located in Glendale in the movie, the residence can actually be found in a hilly section of Beachwood Canyon. Only the exterior of the property was used in the shoot. For the inside of the Dietrichson home, director Billy Wilder had an almost exact replica of the interior of the 1927 house re-created on a soundstage at Paramount Pictures.

“In a Lonely Place” - Villa Primavera

Upon first moving to Southern California in the 1940s, director Nicholas Ray took up residence at Villa Primavera in West Hollywood. He became so enamored of the place that he built a replica of the entire complex, courtyard and all, on a soundstage at Columbia Pictures Studios (now Sunset Gower Studios) for the filming of his 1950 film noir In a Lonely Place. During the shoot, Ray and his wife Gloria Grahame, who starred in the movie, separated under vitriolic circumstances. To circumvent on-set turmoil, the director moved out of the couple’s shared home and into the Villa Primavera apartment set, where he ended up living in what was essentially an exact replica of his former apartment until filming wrapped.

Villa Primavera was constructed by legendary husband-and-wife architecture team Arthur and Nina Zwebell in 1923 and was the couple’s first Spanish-Revival-style building. For In a Lonely Place, the ten-unit complex masked as the Beverly Hills-area “Beverly Patio” apartments where frustrated Hollywood screenwriter Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart) and his beautiful new neighbor, Laurel Gray (Gloria Grahame) lived. While most of what was shown of the apartments on screen, including the courtyard area and the interior of both Dixon and Laurel’s individual units, were set re-creations, the scene in which Dixon returns home after being questioned by the police was shot in front of the actual Villa Primavera complex.

“Kiss Me Deadly” - Hollywood Athletic Club

In the 1955 film noir Kiss Me Deadly, private eye Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) tries to solve an acquaintance’s mysterious death by chasing down clues all over L.A. Many of the sites visited in the movie were located in the Bunker Hill area and have since been demolished. But the Hollywood Athletic Club, where Hammer (spoiler alert!) finally tracks down the “great whatsit” after getting slap-happy with a front desk clerk, still stands today.

Built in 1924 by the Meyer & Holler architecture firm (which also constructed the TCL Chinese Theatre and the Egyptian Theatre), the Spanish Colonial Revival-style structure was the tallest building in the city at the time of its inception. It originally served as a private men’s health club and counted such luminaries as Errol Flynn, Charlie Chaplin, Humphrey Bogart and Walt Disney as members. The building was also the site of the first Emmy Awards ceremony in 1949. After undergoing several remodels and subsequently falling into disrepair in the 1950s, the Hollywood Athletic Club was saved by a preservationist named Gary Berwin in the late 1970s. Today, the grand building is an event venue and filming location.

"L.A. Confidential" - Formosa Cafe

Originally opened in 1939, the Formosa Cafe had the good fortune of being located just steps from the Pickford-Fairbanks Studios, which was founded in 1919 and later known as United Artists Studio, Samuel Goldwyn Studio, Warner Hollywood Studios, and currently The Lot since 1999. Legendary stars like Elvis, Frank Sinatra, Marilyn Monroe, Humphrey Bogart, and James Dean would pop into The Formosa, adding to its reputation as one of Hollywood's most infamous and longest-running celebrity hangouts.

The Formosa Cafe reopened in June 2019 after a stunning $2.4 million renovation by LA-based 1933 Group, which has garnered widespread acclaim for its previous restoration work on Highland Park Bowl and Idle Hour, and recently re-opened the beloved Tail o' the Pup hot dog stand.

Based on the neo-noir novel by James Ellroy and directed by the late Curtis Hanson, L.A. Confidential (1997) earned Oscars for Kim Basinger (Best Supporting Actress) and Best Adapted Screenplay. In a memorable scene set inside the Formosa, Ed Exley (Guy Pearce) mistakenly accuses actress Lana Turner (Brenda Bakke) of being a prostitute “cut to look like Lana Turner.”

“Mildred Pierce” - Pierce House

The most recognizable location from the 1945 film noir Mildred Pierce is easily the beach house belonging to Monte Beragon (Zachary Scott). The unique property was a real home that once stood at what is now 26652 Latigo Shore Dr. in Malibu. Built in 1929 by Frederick Rindge Jr., the residence was, sadly, destroyed during a 1983 storm. However, the house where Mildred Pierce (Joan Crawford, in an Oscar-winning performance) and her family lived is still standing, looking much the same as it did when the film was shot. In the movie, Mildred says, “We lived on Corvallis Street, where all the houses looked alike. Ours was Number 1143.” While the address number she states is correct, the residence can actually be found on North Jackson Street in Glendale. Only the exterior of the Spanish-style dwelling appeared on screen. Interiors were shot on a soundstage at Warner Bros. Studio in Burbank, where the film was lensed.

“The Postman Always Rings Twice” - Sony Pictures Studios

Who can forget the iconic image of a turbaned Lana Turner donning a white crop top and shorts while fiddling with a tube of lipstick at the beginning of The Postman Always Rings Twice? Frank Chambers (John Garfield) and Lana’s sultry Cora Smith plot to kill Cora’s husband, Nick (Cecil Kellaway), in the 1946 film. After their first attempt fails, Nick winds up in Blair General Hospital. The rear side of the Irving Thalberg Building at Sony Pictures Studios was used as the exterior of the hospital in the movie. At the time of filming, the 185-acre studio belonged to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. Much of the MGM backlot was sold off in the 70s, but thankfully, the Art Deco-style Thalberg Building, which was built in 1938, still stands. Fans can catch a glimpse of it by taking the Sony Pictures Studio Tour, or from outside the gates on Culver Boulevard near where it intersects La Salle Avenue. The same building, which houses production offices in real life, also masked as Blair General Hospital in the 1960s television series Dr. Kildaire.

“Sunset Blvd.” - Paramount Pictures

Billy Wilder’s 1950 film noir classic Sunset Blvd. showcases the pitfalls of Hollywood fame through the eyes of faded silent film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson). In a last ditch effort to save her career, Norma heads to Paramount Pictures to speak with Cecil B. DeMille (who played himself). When Norma arrives at the gate, a guard tries to bar her entrance, to which she says, “Without me, there wouldn’t be any Paramount Studio!” Though many fans mistakenly snap photographs of the Melrose Gate that now stands at the lot’s entrance, in actuality it was the Bronson Gate, which formerly marked the front of the property, where Norma admonished the guard. Paramount Pictures expanded its studio space in the late 80s and early 90s, annexed Marathon Street which used to run in front of it, and acquired several acres of land, resulting in the Bronson Gate now being located within the walls of the lot.

The iconic site can be viewed, though, by embarking on a tour of the historic studio. Legend has it that rubbing one’s hands on the gate while uttering Norma’s famous line, “All right Mr. DeMille, I’m ready for my close-up” brings luck in the movie industry.

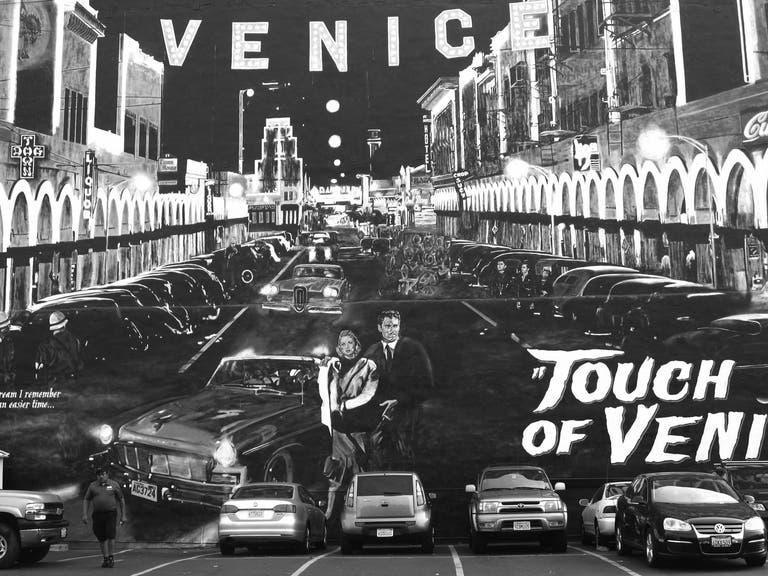

"Touch of Evil" - Samesun Venice Beach

Orson Welles’ 1958 film noir Touch of Evil was largely shot on location in Venice Beach, which masked as the fictional border town of Los Robles. In the dark tale of a narcotics officer’s honeymoon gone wrong, newlyweds Susan (Janet Leigh) and Mike Vargas (Charlton Heston) vacation at the St. Mark’s Hotel. That building is no longer standing but the neighboring property, from which Susan is spied upon, remains intact and is now a hostel known as Samesun Venice Beach. Originally built in 1904, the neo-Italianate columned structure was formerly known as the St. Charles Hotel.

Touch of Evil’s famous opening sequence, which was shot in one long continuous take, was filmed in the streets and alleys surrounding the Samesun, though the area has changed considerably in the ensuing years and is largely unrecognizable from its on-screen stint. In early 2012, artist Jonas Never painted "Touch of Venice," a 102-by-50-foot mural on the east side of the Samesun that commemorates Welles’ iconic 1958 filming.